The meaning of Paul Auster's language

How Paul Karasik adapted Auster's New York Trilogy into graphic novels

When Paul Auster died of complications from lung cancer in April 2024, The New York Times called him the “Patron Saint of Literary Brooklyn” in its obituary. And, while I am not from Brooklyn and don’t believe in calling writers saints, this description fits for a writer who wrote about New York City in a similar way that Raymond Chandler wrote about Los Angeles. Auster used the city as more than a backdrop. It is a character in his work. For more than 50 years, Auster wrote about the mysterious and wonderful, about people coming into contact and “things as they really happen, not as they’re supposed to happen.”

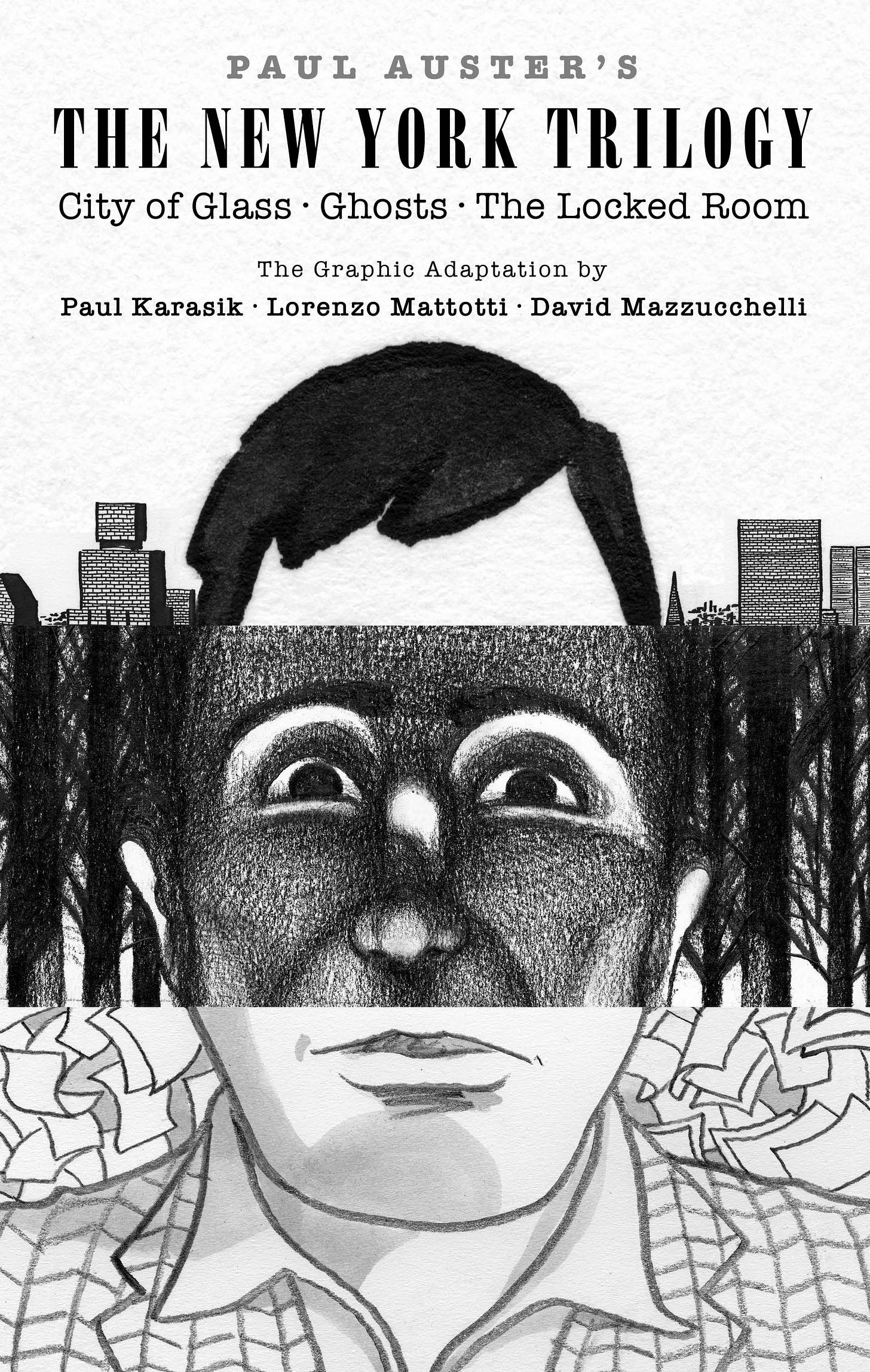

It took a while for Auster to become a novelist. When “City of Glass” was finally published — after seventeen rejections from New York publishers — in 1985, he was 38 years old. A far cry from the next great young hope that every publisher and publication is searching for, his trilogy found a home with Sun and Moon Press in San Francisco. Its two follow-ups “Ghosts” and “The Locker Room” arrived a year later. (Giving some of us, newly 38 some hope.) Auster had been translating, writing poems, reviews, but he hadn’t crossed the threshold from writer writing into writer with a career. The New York Trilogy changed that.

The trio of novels spend their time in the shadows of the noir genre while exploring the meaning of language. Each one centers itself on a character determined to solve one mystery, but who finds something else on the journey, usually about themselves, the world and how we communicate. They’re books about process, which is what set Auster on his own paths for creation. “I’m not just interested in the results of writing, but in the process, the act of putting words on a page,” he told The Paris Review in 2003.

What makes the New York Trilogy stand out is how they function and how they shift with time. The meaning of the novels doesn’t s much as change as it adapts to the reader. Each time I read “City of Glass”, I’ve discovered something new and worthwhile about the story and about myself as a reader. The central themes don’t change, but we change, and, because of that, so does the story.

Auster’s novels have a devoted following, which includes the cartoonist and editor Paul Karasik, who lead the art direction for the new graphic adaptation of Auster’s New York Trilogy. Along with artists Lorenzo Mattotti and David Mazzucchelli, the trio of novels have found a permanent home in a collection of adaptatins that stay true to Auster’s vision while also adding new layers with three distinct styles that bring something different to each story. While Mazzucchelli and Karasik published their version of “City of Glass” in 1994, the other two stories had not been adapted until now, with Karasik directing and also drawing the third novel, “The Locked Room”, himself.

Karasik won an Eisner award with Mark Newgarden for “How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels”. He has contributed to The New York Times, The New Yorker and was an associate editor for Art Spiegelman and Françoise Mouly’s comic anthology RAW.

So let's talk about this illustration, because it starts in, what, 1994 is when the first book comes out of this, when “City of Glass” is done? Is that when you first do it?

Yes, “City of Glass” came out in 1994.

So explain to me how you get a project like this: what is the genesis?

Well I'm just trying to figure out how to tell this succinctly and briefly as possible, but, in many ways, the coming about and the evolution of this book is sort of like a Paul Auster story in that it is riddled with improbable coincidences and unpredictable timing that now seems completely inevitable.

It goes back to the early 80s when Auster had just written “The New York Trilogy”, his first important work of fiction, and I was teaching at a private school in Brooklyn Heights. His son was in my class — I was teaching art— and I had heard that this young author, he was older than me, who written some books and I thought, "Okay, I'll read the books." Then, when he comes to a parent-teacher conference, I can sort of, you know, kiss his ass a little bit, fawn over him, but when he came to the parent-teacher conference and we never once mentioned his writing because there was so much more to talk about with his son, who we were both, at the time, very charmed by. But I read books and the first one, “City of Glass”, you know, I always kept a sketchbook and I had made some notes in it thinking about how this could kind of be a comic. I'd done some sketches, kind of just thinking with paper and pencil, and then I never thought about it again.

So then we jump forward, I don't know, maybe close to eight years later, something like that, seven years later, and I've moved to Martha's Vineyard and the phone rings and it's Art Spiegelman, whom it's not unusual for us to chat every once in a while, I had been the associate editor of RAW magazine, I had taken classes with Art and he was really my mentor and my friend. So he calls and we're sort of shooting the shit and he says, “you know, I was calling because I was thinking about you, this book project, I'm helping an editor develop a series of contemporary noir novels translated into or adapted into comics, and we chose one that was really impossible to do to start with just as a test and now I don't think we're going to be able to do it. Several artists have tried and it's not really working out.” And he said, “you know, I thought of you, this might be in your wheelhouse.” And I was like, “well, what's the book?” And he said, ‘City of Glass.’ And I said, “oh, well, let me go down to the basement and get a sketchbook I've already started.” And so, you know, just as “City of Glass” starts with a phone call, my serious story of grappling with “City of Glass” starts with a phone call too.

That book happened kind of magically because David Mazzucchelli, the cartoonist, was already kind of on board as the artist for it, thank god, because David Mazzucchelli is one of the greatest of living cartoonist and, most importantly, he had cut his teeth at DC and Marvel's drawing Batman and Daredevil, so he knew how to draw the hell out of New York City, which was a very fortunate thing for “City of Glass” because I certainly couldn't do it. So I did a sketch version of it, David revised it, we got it approved by Auster, and Spiegelman was involved too, and David drew it. The whole thing happened, from start to finish, it felt like less than two years. Everything clicked. I kind of knew intuitively what I was doing out of the gate. There's a very difficult section in chapter two of that book, it's a monologue, and how can you possibly adapt that monologue? So once I cracked the code to that visually, how to translate it from the written language into a picture language, then everything fell into place after.

How do you take somebody else's work like this, which is its own canvas that is large in scope but at the same time really small, and translate it onto a page? What is the first step for something like that for you?

With “City of Glass”, I just knew what it was really about to begin with. I understood it on a very deep level. I think that's the first thing that the adapter needs to do: to have a fundamental understanding of what the book means to them and what is sort of the emotional core of the book, as well as the intellectual core of the book. Then you can begin to reconstruct the structure using a different set of tools and building materials while you're looking at the at the book that's already been built.

It feels explore more because you're kind of confined to a subject, which means you’re allowed to go off a little bit and explore. I think of Shakespeare and his stories: he has a very clear audience and subject and a structure that he has to adhere to and within that, though, you end up with almost more beauty because you have to create something within those constraints. I'm wondering if that's something you found.

You use Shakespeare as an example and it's interesting example. So, you know “Macbeth” is “Macbeth”, but you know Orson Welles's “Macbeth” is very different from Kurosawa’s “Throne of Blood”. Both of those guys had different ideas about what “Macbeth” is about, right? And it's like they're core idea about what the messages is, is quite different. So that's the answer to part of your question. The other part of the question is how much leeway we were given doing the visual adaptation. So Auster, in his typically generous self, said, “well you guys can do whatever you want to do but you can't touch a word of my language. There's going to be a lot fewer words, but every word in the book has to be a word that I wrote.” So that actually was a restriction that turned out to be a terrific help for me because it allowed me to be faithful to Auster's work in a genuine way and because I didn't have any choice, and so that was really kind of liberating in a fashion. Using that constraint then, it kind of forced me into some interesting corners that I had to find my way out of, and, in grappling with the material, I got much, much closer to it.

Yeah. Well, so I guess, so when the first one was done in '94, when is the second?

So the first one came out in '94, and then the second two, this is their debut.

Why the delay?

Well, I hope this doesn't sound glib, but it took me decades to understand what the other two books were really about.

That's not glib. I think you have to be of a certain age almost to kind of understand each one.

I traveled for years with both of those books in my in my suitcase, especially like if I was going to Europe often to teach comics and that became sort of a ritual: bringing those books and reading them and reading them and reading them and rereading them. And I couldn't quite figure out the core of them the way that I could immediately with "City of Glass", which is the meatiest the meatiest of them all. It's the most sort of plot driven and a little more linear throughout. "The Locked Room" has lots of digressions and it's kind of foggy and "Ghosts" is kind of the fulcrum of the other two books. It took me a long time to figure out what I thought the emotional and intellectual core of those those two other books were and, once I got that down, I called Auster up and I said, "you know, I have been thinking about doing adaptations the other two" and he said, "well that's interesting." I said, "but I just want to make sure that this is what I think they're really about," and I explained to him what was on my mind and And he said, "Oh, you got it, just stick with those ideas and you'll be fine."

With drawing those, there's such a different style to them. Is that influenced by your understanding of it? How did this style evolve for you?

The first book book, "City of Glass," is drawn by David Mazzucchelli, who is, as I said before, one of the greatest living cartoonists, and he's got a very distinctive style and approach to drawing. When that book came out, the graphic novel revolution, as it were, had not begun. And there were no graphic novel sections at the library or the bookstore. There was "Maus" and "Tintin" and that's about it. It didn't really get a lot of general interest. However, people who are into comics noticed that book, and it's become sort of a cult classic over the years. And especially as Auster’s reputation grew, and Mazzucchelli’s notoriety grew, that book is, for many people, a very important book, sort of a gateway, graphic novel for adults.

So I knew that the other two books had to look different from that. The three different stories are very different, so they require a different graphic approach and they should look as different from the first book as possible. The second book, "Ghosts", I kind of knew that that was going to be more of a illustrated text mostly, almost like a picture book, but you notice that it takes some little jigs and jags throughout stylistically, but I knew that it was primarily an illustrated book and I knew Lorenzo Mattotti a little bit, I'm friendly with him. I lived in Italy for a year and our paths crossed and I knew that he was a fan of "City of Glass" and he's a great illustrator, The New Yorker cover artist and he's done comics too, but primarily he's he's draws big beautiful juicy pictures and I knew his black and white work is just stunning. So, I didn't have to twist his arm at all.

And then with the last book, that kind of went through some various permutations with alternative artists. And then, finally, Aster just kind of insisted that I just draw it. He said, "you know what you're doing, you've done the whole sketch, you've done the sketch, just draw it." And I actually had never considered that I would be the artist for it because I don't have a great deal of confidence in my drawing skills.

Really, why?

I just don't. He had confidence in me.

I'm wondering why the confidence wasn't there for you.

That's just sort of a personal drawing problem. It's taken me a long time to feel any confidence in my drawing.

I probably shouldn't admit that. We should probably skip that. Let's just put it this way: I did the best I could do and I'm proud of the work that I did.

Well, I'm asking mostly because I remember that the pages about the with a wine glass So that those pages where I was like, oh, this is fascinating and also extremely confident, you know, to go that far into a swirl. You know what I mean?

So here's the thing. Let's see if I can explain this. One of the first things that I said was that “City of Glass” felt like it happened because Paul Auster had written it. And this whole evolution of this book, the decades that it took for me to understand the core idea, Lorenzo Mattotti coming to a talk in Brooklyn about “City of Glass” and our paths crossing, and, then finally, decades later, Auster insists just saying, “Paul, just draw the thing.” If that had happened five years earlier, I wouldn't have had the chops. It's the way everything happens in those books that seem like coincidence, but it's something that's just part of being human.

I'm certainly not a religious person, barely a spiritual person, but, every once in a while, these crossing of these paths and time coming in and extending and then contracting and then suddenly it was like the time was right and I had the time and I sat down and drew it and I could do it.

So what finally opened up the other two books for you? What did you finally get like what was the what was the missing link?

Well I'm reluctant to spell it out.

I think those are personal books. I'm wondering if they're different for me.

I'm reluctant to spell it out because I think that part of the pleasure that comes from reading the books is to just experience. I feel like it's not the plot I'd be giving away, but it's, well, wait a second, maybe it is the plot, but it's like the comic’s plot. If story is what happens, and plot is how it happens, I know that's talking about glib statements, if you were to hold somebody to that statement, it might be hard to prove, but I always kind of like the way twinkles rather. If story is what happens and plot is how it happens, if I was to explain what I think these books are about, it would kind of blow the plot. But once I figured out what they were and embedded them in some obvious ways, and in some very, shall we say, hidden ways, visually, then that becomes part of the pleasure of opening the book for the first time and reading it. And I don't want to spoil that for anyone.

When you compile three artists like that together this, I want to know the actual way a book like this comes together. How are you managing all of this?

Let's start with the physical process: I'm doing a thumbnail sketch version not of all three books and then I'm doing a fairly substantial sketch version based on my thumbnails and building the script on a Word document and then each artist gets those, including myself. I figured out what the words are and what the pictures are and then I give them to the artist to finish off. Now that said, with David Mazzucchelli, in some places he just did my drawing, a finished for version of my drawing. In other places, because he's such a masterful artist — and back then, in the early 90s, my drawing was really not that good — and he knew how to draw New York City, and he brought some air into the book that I couldn't, I just didn't know how to. With the second book, I gave the sketch to Mattotti and he understood exactly what I was after, but because he is such a sophisticated draftsman, he took my drawings as the as the sort of diving board.

So the layout is mine, and the words on the page are Auster's that have been whittled down to what I need them to say in conjunction with the picture, and then Mattotti just had fun and did these magnificent drawings.

For myself, I followed the same process: did the thumbnails, a full sketch, the script and then the final drawing.

How long does one of these take from start to finish then?

Everyone works at a different speed. “City of Glass”, start to finish, seems like two years, but maybe it was more like two and a half years or something. "The Locked Room", from start to finish for me, let's say when I actually decided that I was going to do the final drawing, that was probably two years of work for me. I'm very slow and I'm very analog.

Normally I would end this post here, but when it comes to Auster, I can’t. While researching these books, I came across an interview with Auster from 1992 with the literary journal Contemporary Literature, which was distributed by the University of Wisconsin Press (thank you, JSTOR). The interview is fascinating and wide-ranging and Auster is a willing interview subject. But early on the interviewers ask him about his interests and what he’s tackling in his fiction. Essentially, they ask: “Are you interested in tracking down the sources of these recurrent ideas and motifs?” Which Auster gives a beautiful, and long answer. But it’s the first few sentences that struck me as important when looking at his work and this graphic adaptation of his most famed work. He says:

“Writing, in some sense, is an activity that helps me to relieve some of the pressure caused by these buried secrets. Hidden memories, traumas, childhood scars — there’s no question that novels emerge from those inaccessible parts of ourselves. Every once in a while, however, I’ll have a glimmer or a sudden intuition about where something came from. But as I said before, it always happens after the fact, after the book is finished, at a moment when the book no longer belongs to me.”