It took a while, but here we are. The return was inevitable. Actually, it wasn’t.

I’d had many requests for interviews pushed back or cancelled or ignored. I’d also not found as many books in the final few months of 2024 that sparked an immediate need for some introspective reading. This says more about me than the writers.

I also took a teaching job last year and I was worn down from trying to get high schoolers to read. Some day I will write about the recent disappointing (but not surprising) test scores for American children and my own experience. (Hint: it’s not the teachers.)

But back to our not so regularly scheduled programming.

Here’s a secret: I once wanted to be a poet.

My first love in reading was and is poetry. It’s the form that brings me the most pleasure. I also know I can’t write it well (or well enough) and don’t really understand it as a form. I will read Richard Hugo’s “Selected Poems” or Robert Frost’s “A Boy’s Will” or Eliot’s “Four Quartets” over almost anything else any day. For years I kept pocket copies of Walt Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass” and Yeats’ “Collected Poems” next to my bed because picking a poem and reading one comforted me. But, for whatever reason, whenever I get a copy of n+1, The New Republic, The Believer or The New Yorker (I am really outing myself here), I don’t flip to the poems. Often, I skip over them. They don’t feel in place in those magazines even though they’re vital to the poetry ecosystem. It’s just not for me, and, because of that, I miss a lot of modern poetry. I miss it all, in fact.

Until now.

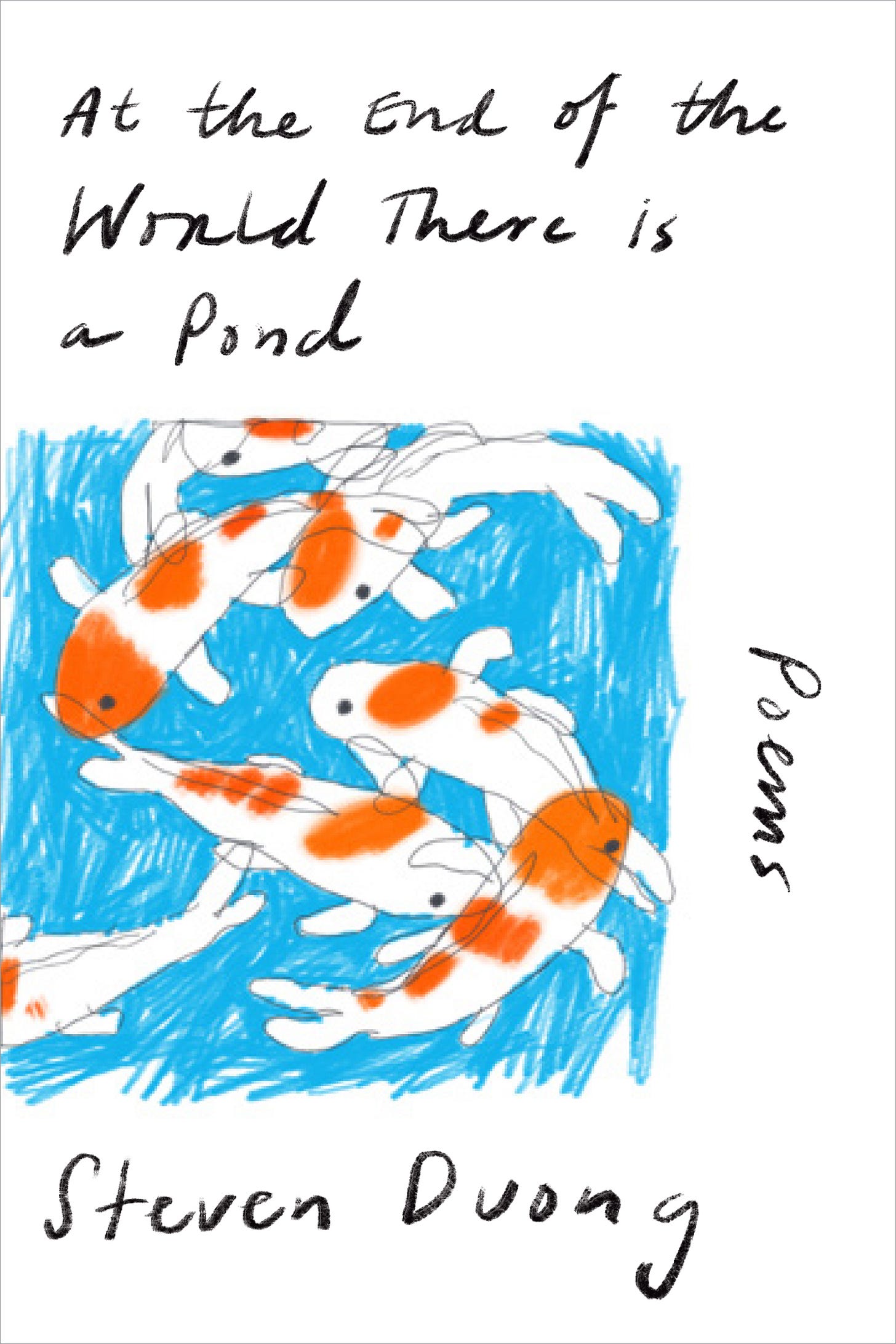

Something sparked my interested when reading about Steven Duong’s debut collection “At the End of the World There is a Pond.” It may have been the title. It was probably because I was teaching poetry to high schoolers, though. When I got a copy, I opened it and felt seen. I could picture Duong on the other side of the page speaking to me through his poems. I didn’t get nearly any of them on the first reading — the first quiet in contemplation reading, I should say, where no children were around and I wasn’t being hurried into the next chore or job. With each successive reading, though, I found myself looking in on Duong’s life. The poems radiate personality and personal history. The white space on the pages, the use of space, and the formulas he submits his ideas through settle into a disjointed pattern that reminded me that the best art makes us feel something because it is also feeling.

Take, for example, the poem “The Black Speech.” Duong starts the poem in one form that appears simple, but then the poem bursts open and starts almost breaking down and going wild on the page. There are indents. There are white spaces between words. It’s two poems having a conversation. He ends it with this couplet:

there is no language alone

that can eulogize the living

The end came and awoke me. I had to go back to the beginning to find out how we got there, which, to me, is the sign of a great poem (or any art). As I reread, what made this so striking is that the poem starts in second person. It’s talking to you, the reader, and then it shifts to something else entirely, leading you down corridors of revelations, which is what Duong’s collection does so well: brings about revelations about him and also the reader with each pass.

Duong is the Creative Writing Fellow for Poetry at Emory University. This is his debut collection of poetry.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I read these poems and felt they were personal to you. I like to think poets are always personal and all writing is a little bit personal, right? But these felt, after the second and third time through, sneakily more personal than I anticipated. Is poetry for you a personal experience?

I like that word “sneakily” because my favorite poems are the ones that kind of sneak up on you on a second read or something like that. I would say, poetry is personal to me.

I think I first came to poetry in the way probably a lot of people come to poetry, which is the sort of like diaristic, confessional, sort of teenager in a bedroom kind of poetry?

Listening to to emo music, writing a poem. Kind of like Taking Back Sunday as poetry, but it's really not.

Taking Back Sunday, wow, 10 years isn't that wide [Duong is ten years younger than me], I guess. A lot of acoustic guitar, but trying to play the electric songs on the acoustic guitar.

I would say it was important to me that the poems in this collection feel more immediate. I think there's a lot of poetry I like where they're doing so much on the level of language, on the level of the line — there are these kind of like acrobatics of syntax and rhythm and sonics. There are some poems that really strike me, but sometimes they leave me cold, and I really didn't want the poems in this book to leave anybody cold. Maybe the the personal thing you are kind of poking at is maybe that impulse to feel immediate on the page and to not do away with figurative language or images, so they're sort of crafty elements.

I don't know if I put that in quite the right way.

It is immediate, but for the personal thing it took me the second read because the first time I read it quietly in my head. And then the second time, I read it out loud, which is what you're supposed to do, right? But reading out loud makes you start to see the little patterns that you're playing with. You're playing with a lot with white space so how do you view space in a poem? And how does it connect to that immediacy and that personal? Where are you drawing that line like where are you feeling like that lines for you I guess like where are the two worlds meeting?

I think I think in terms of I'm just thinking I'm just actually I'm thinking about like the first part of your what you were talking about which is like sort of like the white space…

I think some of the poems in the book, they're distinct formal poems. They're like these sonnets, which there's not white space. They're just these boxes, right? Then there are these poems that feel like slightly more disjointed or fragmented. I guess that is reflected in the way they are spread out across the page. But I think it was important for these poems throughout the collection to have that sense of contracting and dilating. Maybe that's kind of a weird way to put it, but I felt like there's something about breath, perhaps — like spreading out and coming back in, spreading out, coming back in, the order and the constraints of these like boxy formal, craft object type poems, and the poems that like just spread out on the page.

But where does that line connect for me?

I describe in one poem this hallway with a bunch of doors (“Novel” pg. 81). That's kind of how I think about my poems in general: as these hallways. There are all these doors and some of them you can see a little a sliver of light through it or something and some are cracked a little bit more. I think it was important to me that they there's so much possibility. It's hard to end in a definite place and still feel like at the end of the poe that there's something like possibilities, that there are still things swirling around.

The doors thing is interesting because you kind of open doors a little bit somewhere in a poem and then you'll pull back — I'm thinking about “Ordinance.” That's the one that I think is like the one where I was, oh, I get it now. I saw the little spots where things were opening into the personal, while not revealing everything?

I have to teach Whitman to juniors in high school and he comes after teaching Emerson, which is what we do purpose because one guy is formalistic and threw a grenade into American culture, and then the other guy is like, I'm going to throw a grenade into everything, I'm going to take the epic and turn it into a working class poem play with form. And he plays with form in ways in the white space in a way and it's like still mind boggling to me. I still read it and I'm like, I don't know what the fuck is going on. I do know, but I don't know.

That's the thing. That's so important to me, though. With poems it is to know and not know. This is something I couldn't have imagined like even by six years ago, but my mom recently told me that she had read the book and English is her second language, but she's fluent, and she sort of says all the time that she doesn't really understand what's happening at the level of the language, but she feels something. I have to try to tell her that that's probably how most American English speakers also encounter poetry.Even when you're encountering poems even in your native language, you're not being relayed information necessarily. There's some things you're grabbing onto and there's some things that are escaping you, but the best poems leave you content with that feeling, I think.

How long did this collection take you to write? It seems like it's it's immediate, but also there's yeah, as I said, like I think there's a lot of craft involved here, so I don't think this is an immediate poem poetry book, right?

I would say the oldest poem or the first poem to be drafted in the collection, before I had a sense that it was a book or a collection, was in maybe like 2017 or 18 or something like that. A good time ago. The most recent poem I drafted in the book, probably those two “Novel” poems at the end, maybe those are like 2023. Those were probably after the book was accepted for publication.

So something kind of fun for me reading it that maybe is not part of like everybody's reading experiences is being able to see the way my writing and my voice has changed and or stayed the same. A lot of the poems also kind of follow like this sort of travel narrative — or at least the locations are are important — and the sense of place is important. A lot of that the traveling in the poems in the collection are from like 2019, 2020, right before COVID. I think that was when I was accruing poems without a sense that there was a book emerging. Then all these little patterns emerged. You put the poems next to each other and you see things sort of cropping up. Like, there's sequences of poems for sure, but there are also these weird little mirror moments that were at first unintentional, but then kind of guide the process once you find them.

All writing goes through the patterns in your life — where you're imitating other people or finding your voice — and then you find little pockets of things where you go, that's me, that, right there, is me. I can read something I wrote and see the little moment — two sentences — and that's what I wanted. The rest is me trying to get to that point. And I felt reading this that I could tell when you found a poem and found the point where you knew it hit the mark for you, for the immediacy you were looking for. Do you find yourself doing that?

Yeah,I think I think because the poems were written across a span of time — I drafted one poem in like 2019 — and I felt in 2019 that, oh, I've arrived at that moment. Actually, that poem, the one with the bombs, “Ordinance”, maybe that was more like 2020 or 2021.

I could feel the COVID in my blood cells. I remember that there were some poems in here that I was like, oh, man, I feel this from that.

I think there's a lot to be said for the effects of COVID and quarantine had on people and writers and art. That sense of going from traveling, which was something I hadn't really done, mostly in Asia for months. Going from that to the pressure, I guess, of quarantine. For poems, I feel like the click, the scrutiny or the attention, that I place on those events, which are sort of like memories, feel really pressurized maybe because they were written at that time: what else can you do but think and write about things you used to do? Read, of course. I think there can be an obsessive, maybe, quality to some of the voices and some of the poems.

For those early poems, did you find any major changes as you started the editing process?

Honestly, there are, of course, moments from poems from way back that I have altered or changed, but, in many ways, I try to resist that impulse. It's one of those irresistible impulses. The first impulse is to cringe when you encounter whatever you consider to be your juvenilia — my juvenilia meter is like a month ago.

But then I had a corrective impulse too, which is to filter everything through my current understanding of what a good poem is and I'm not sure that would allow those older poems to be stronger necessarily, and in some cases for sure. But it's one of those things where I feel like it in maybe five years from now that won't hold. So why am I subjecting these older poems to this scrutiny of the 2023 or 2024 poet/slash editor, myself? Then there's like a specific poem, one of the “Novel” poems, the page 59 “Novel” about the son writing a novel, I thought these thoughts profound:

“I believed myself the sole/ practitioner of this magic”

This to me was maybe the second to last poem I wrote for the collection and this feels to me like an attempt on my part to speak to maybe some of those speakers or even like the poet that wrote some of the other poems in the book. It's like you read their work and it's your old self and you cringe and they're perhaps misguided or just didn't have like the exact understanding of craft necessary to answer the questions that they're trying to answer, but it’s so clear that person loved poems and writing poems and literature and trying to arrive at those answers and was dedicated to the quest of trying to arrive at the answers to those questions, or even just to articulate and impose the questions on the page. It's self-critical, I guess, but I think it does hold some kind of compassion or something like that for these other [poems].

I'm also thinking though, like a lot of poets go in the other direction too. Once you understand the craft, you go the other way and you break every wall like W.S. Merwin. His later poems become something else, there's like no punctuation.He broke every barrier. I gave one of his poems to my freshman and their heads exploded. It was a lot of fun for me. Seeing them try to navigate this thing was exciting because he's going so far away from what they expect, which you do too, and they are so new to it that they can almost meet in the middle.

That's really interesting that you say that because I've had that experience with teaching, but also knowing friends who are, you know, again, either English isn’t your first language or you're just approaching poetry for the first time, but you don't have to necessarily reteach a native Chinese speaker to really have to break down these sounds. They're already doing that because English is so fucking confusing. I bet encountering Merwin for the first time, and if that's one of the first poets you encounter, you're like, it's perfect, because you have to take the baby steps and a person who's been reading all kinds of other poetry would sort of like have to replace themselves into that position.

You said you had good teachers like that gave you all this information and I almost feel reading this that you've taken all that and kind of like again, like a bomb at all of it. This feel like somebody with a ton of information and now decides to destroy it? At times do you feel that way?

I especially feel that way with like the more like there there's like these Ghazal, and there is like that one called “Ho Chi Min City” and these couplets that end all on the same refrain and it is a strict form. It's very specific and when I teach it, I'm like, “it comes from the Urdu and it's made its way into Arabic and now it's in English, and now you have to write it, go home.” I know that form so well, but these are fucked up Ghazals. You don't really want them to look like this.

The couplets are supposed to be like self-contained. Every couplet is supposed to be sort of its own stand alone. You could take that couplet and it has a lot of meaning on its own and and it's through the accumulation of the couplets that you arrive at the end result of that type of poem. But, in those poems, I feel like I am, as you said, throwing a bomb at it, and I sometimes feel like I'm doing some kind of violence on these formal traditions or whatever. But, oftentimes it's things like by not making each couplet its own thing, I'm just letting everything kind of blow.

And then when you read it, you're not thinking so hard about things like, oh, he's done this thing where like every single thing ends the same. Like, oh, he's done this kind of rhyme or whatever; oh, this is clearly a sonnet; look at the pentameter, look at the way it's crafted.

I think that the trick is still somehow to have a distinct voice and somehow remain kind of, again, immediate and conversational.