Satirizing in a gentle way

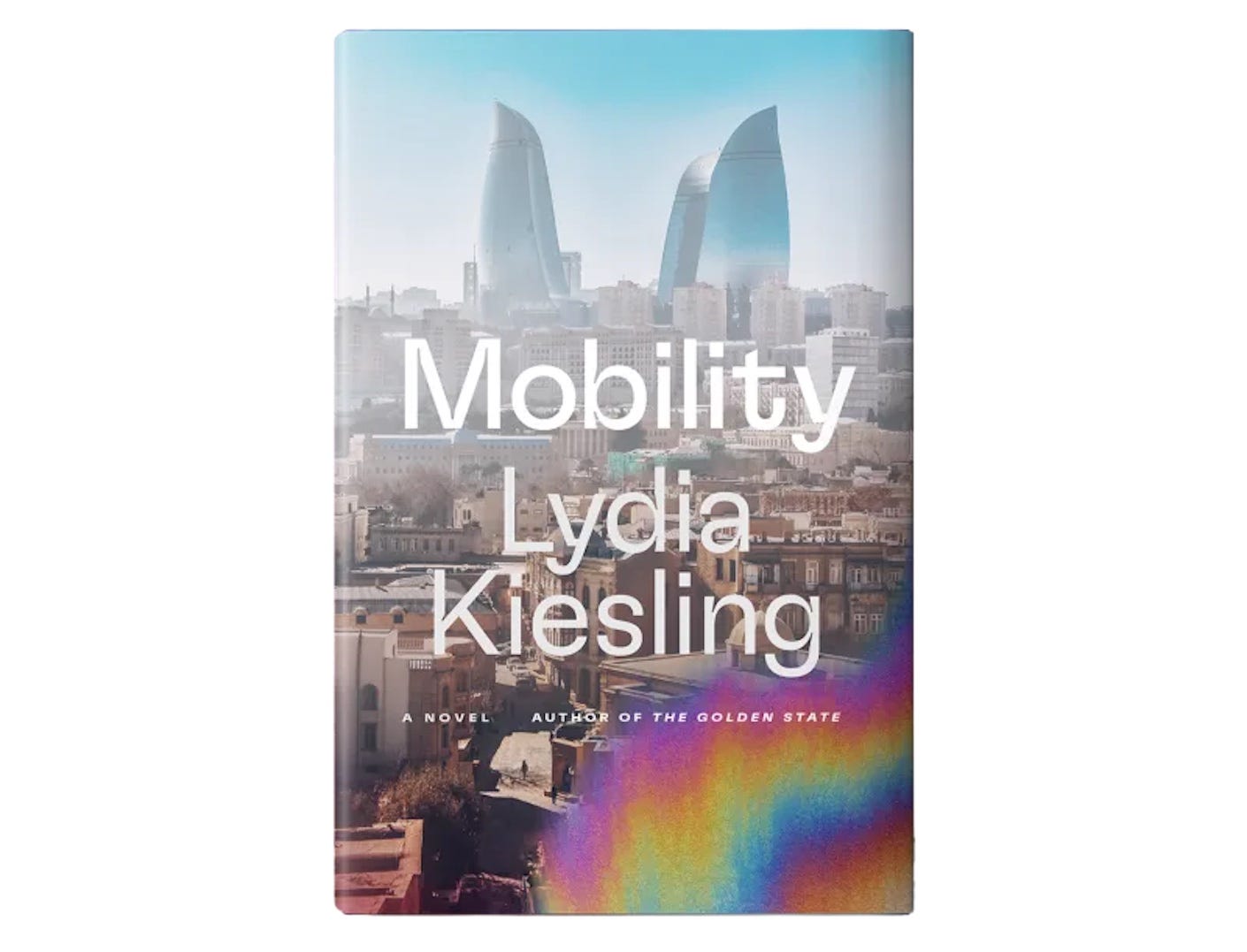

An interview with author Lydia Kiesling about her novel "Mobility"

FIRST GUEST POST! And I’m so glad it’s by my friend Diana Valenzuela. Please enjoy her interview with author Lydia Kiesling.

By Diana Valenzuela

It’s 2023 and no one I know uses the term “girlboss” genuinely. When the concept was coined about a decade ago, girlbosses were celebrated as women in business who upended male-dominated industries. Sounds great in theory, except girl bosses wore out their welcome by tending to think that they were revolutionaries for existing. A textbook girlboss could be participating in any number of morally bankrupt schemes, but could also see themselves as an example of righteousness.

As much as I throw shade, I also embody the girlboss. I rarely use my experience as a woman of color to uplift or help anyone. There are times when I ignore the crime, racism, and brutal living conditions within my own community to play swipe games on my phone. I’ve impulsively bought fast fashion while also fully aware that those glittery heaps of polyester have done untold damage to the planet and humanity. I’ve flown to gentrified cities and enjoyed curated vacations, all while skirting around local slums. When I see someone in pain, I often turn away.

I like to ignore these blemishes upon my personality, but recently, a text reminded me that those weaker facets exist. Lydia Kiesling’s novel Mobility reflected my own myopically individualistic tendencies in all of their ugly glory. The novel follows Bunny Glenn, who starts as a bored teen living abroad with her Foreign Service family in Azerbaijan. After years of listlessness, a mid-20’s Bunny lands in Houston, where she stumbles into an oil industry career. Kiesling chooses to distill massively complex themes and intricate geopolitics through Bunny, who mostly cares about the status of her own job, her workout routine, and the calorie content of Trader Joe’s salads. Her selfishness is my selfishness, magnified and set against a background of capitalism and climate change.

Recently, I caught up with Kiesling to ask about her process.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In Mobility, the protagonist’s name is Bunny. Why name her after a prey animal?

The first scenes from the book that appeared to me were somebody who had a teenage upbringing very similar to mine. Somebody who was similar to me at that time — on a plane going somewhere that was really unfamiliar to her. I knew I wanted her to go to elite institutions and be kind of a dumb ass. My issues with Bunny actually become more real the older she gets. When she's a teenager, I have a lot of sympathy and empathy for her because she’s very similar to how I was as a teenager.I wanted her to have a name that was defenseless sounding.

One of the things I wanted to think about was how white women — especially liberal white women — are conditioned to see themselves as helpless, innocent, and well-meaning. I wanted a name that conveyed that. Also, people didn't take her seriously as a kid and they gave her a name that she embodies in some ways. So I knew I wanted her to have a name like that.

At around the same time, I listened to the audiobook of Oil by Upton Sinclair, which is one of the great American oil novels. There Will Be Blood is based on it, but the film deviates so far from the novel. They're basically two different works of art. The main character in that book is 13 when it starts. He's a boy called Bunny, that's his nickname. He's this son of this big oil magnate. That book is his political journey. He meets the oil workers in his father's oil fields, he learns about socialism, and he becomes this pretty standup guy. But still, he's had such an easy, privileged journey. He makes the most of it when he becomes an adult and sees that the world is really unfair. So I wanted to do Dark Bunny. What does Bunny look like if Bunny's a woman? And what if it's not in this era in the twenties where there's a lot of violence and awfulness, but also some kind of hopeful struggle? What if instead it's in our era, where the Soviet Union has proven to not be a sustaining enterprise and really rampant capitalism is one?

The name Bunny also works for her environment. At the beginning, she's attending boarding school. In those privileged spaces, women often will have silly names that aren't very practical.

Bunny feels actually a little bit out of place in that environment, but when she meets the children of the truly super rich that name still lets her seamlessly be a part of that world in a way that’s attractive to her. When my dad was posted to Armenia in 1997, the federal government paid for my boarding school tuition. I went off to school and there was a woman on the board whose nickname was Kitten.

Bunny reminisces a bit about her life as a younger child. She had been a more serious kid, but you chose to start the book at a point where she’s no longer serious. Instead, she’s rather listless.

Part of it is just that I could so clearly remember that feeling. I'm going to be 40 in a few months, so I'm moving into a very different phase of life. Looking back on earlier years, I’ve been really surprised by what completely disappears from memory, versus what stays. I remember those feelings of wanting so badly to be in the stream of life, but not really being able to be in it yet. Also, having no energy to improve yourself in any way other than spending a tremendous amount of energy on thinking about how you look. It really surprised me as an adult. Now, I have daughters of my own and I think a lot about what I want to impart to them and what I want to model for them. I've spent a lot of time thinking about how many strong memories I have from earlier life that are just being so preoccupied with how I’ll be seen, what I look like, what my body looks like. That was something I wanted to convey. I didn't really know what was going to happen with the rest of the book or where it would go, but I knew I wanted that feeling to be in there.

In your writing process, are you more of somebody who maps out a whole book in its entirety?

No. I really wish I could. That seems like it would solve everything, but whenever I've tried to do that, I just get even more confused and depressed. I think in my case, a book has to teach you how to write it. It has to teach you what it's about as you're going, which is so painful. But you kind of inch forward. In my case, I start with those things that feel urgent, that do feel easy to write. Describing those teenage girl emotions was effortless to write. Then I’ll say, OK, what are the themes that emerge from this? What comes out?

I saw a lot about power, feelings of hierarchy and belonging, and different directions of desire. I tried to go from there. I built it little by little, but it took a long time before I really understood what the book was. That’s a miserable period, when you're fumbling around and you don't know what you're doing. You're just hoping that something will occur to you pretty soon.

As Bunny grows and eventually stumbles into a career in oil, she confronts huge ideas that are really hard to digest. Was it tempting to turn her into a mouthpiece or make her become more justice oriented?

Only in that it was painful to know that I was writing into the worst version of reality. It hurts to think that, even in this work, I'm challenging the status quo only by identifying it really and satirizing it in a pretty gentle way. So that part was hard, but at no point did I ever think, What if she has an awakening? Then, the book wouldn't do what I wanted it to do, which was to expel some of the disgust that I feel both for myself and things that I have seen around me. And I feel like I didn't have what it takes as a novelist to make a convincing sort of change. When I thought, What if the character was someone different? or What if I had included people who were struggling against this? It felt like it would ring inauthentic. The closest I get is that you hear some other voices and points of view from other characters. That was how I satisfied myself. But even then, those are limited perspectives. There's not anyone in the book who is truly struggling against this every day.

One thing that frustrates me about my own book is the Charlie character. He represents a different point of view.Initially, I wanted to point out that there are people who have ostensibly good politics who are still complete pieces of shit. That's another thing that can be challenging and confusing about social movements: separating how we think about people individually from how we think about ideas. But ultimately, I think the book is too affectionate toward him and that's the way men get away with being seen more positively, even if they've made really big mistakes. But the book is much harder on Bunny in the end. Iit gets very meta, but sometimes I think, Oh man… Because people say, “Charlie is lovable.” I know — it's not fair.

Bunny kind of goes in this “girl boss” direction as she moves through the oil industry, which I thought was horrifyingly realistic. But I could also understand that she’s making the best of her situation. She climbs the ladder because it's where she's ended up.

There was a time, when I was probably in my late 20s to early 30s, when I would get together with my friends from college. It felt so urgent that we needed to be really on our way to doing something or being something. I could feel myself in some of the jobs that I had at that period — I’d think, There's no other thing that I can do except this thing that I'm doing right now. So I’ve got to do a really good job. It's really a powerful urge. It's hard to work against that feeling once you're in it. Also, so many jobs are so made up. I remember from that time period, my friends and I would all tell each other what we were doing, and we'd ask, “What is that?” Some of these jobs get invented in real time, but once you're doing them, you think, Well, this is what I do. I'm really good at this database software or whatever the fuck.

As Bunny ages, I started to feel more critical of her, maybe because she does gain some power. But increasingly, she also uses all of her energy to examine herself and the people around her. She's maybe smarter than I initially gave her credit for and she has a laser-sharp ability to assess people.

Sometimes, I think that's such a feminized trait. Not to say that only women are observant, but sometimes when I talk to neighbors, relatives, or women who are older than I am, they’ll give you the most razor sharp analysis of a family dynamic or another neighbor situation. Something that involves interpersonal stuff. That observation can come from someone who hasn’t ever had a high power job or made a lot of money. So Bunny has that ability. And in order to be the person that the book follows, she has to be very observant and trustworthy in some ways. On the other hand, you think, What isn't she seeing? She’s focused on the people around her. If there's something that could tell her more about the world that she's in, she chooses not to look at that, chooses not to pay attention to that. Anything that's more systemic feels too difficult and too much to manage. She keeps her focus very narrow, but then within that narrow focus, she’s very astute and observant.

At the end of the novel, do you think Bunny regrets the work she's done? Because I didn't get that sense.

I think that she can still rationalize it into her broader worldview, which is that these things are already set up, these structures were already in place, they couldn't be changed. She’s really invested in not blaming herself.

One of the things that's sort of a side note, but felt important to me, is that the company [Bunny works for] gets acquired by a branch of Exxon. After that, she gets let go. She puts so much effort into making the goals of that hierarchy into her goals, she wants to match that institution. And in the end, the institution didn’t love her or take care of her.

It's very convenient that I don't really go into detail when describing that time period. But it suited me better to have it be very muted. I do think people go through very long periods without saying, “Maybe I made the wrong choice.” Because that’s really hard to do.

In Bunny’s future, the effects of climate change confine her to the area of Portland. She’ll never see her brother and father [who live abroad] again. In that reality, does the world become more community oriented?

I hope so. That's the hardest thing for me to think about when we talk about what we’ll need to do, especially in the west or in the global north. The thing that feels the hardest is that we may need to give up the easy ability to go around the world. People won't see their families, especially recent immigrants. That's really serious. There might be a world where there are restrictions on flight in order to prevent the worst. But I think that a lot of the effects of climate are only survivable in individual communities because communities come together and help each other out. It has to be that way. That would be an upside — if there's sort of cohesion and closeness, but some people don't have that mindset, because American society is pretty individualistic in terms of our public policy and how we’re conditioned to think about our obligations to other people.

Bunny’s in this class where they go into a bunker mentality. I think a lot of people will do that. Even then, you can't be in your bunker by yourself. It'll be so boring. So maybe we have bigger enclaves. Octavia Butler wrote a very prescient, terrifying version of that [Parable of the Sower], where it's just individual neighborhood enclaves. In that sense, it's in her telling, it's very scary and dystopian. But then the other side of that is like, Oh, what if communities are helping take care of each other?