Can magic save us from isolation?

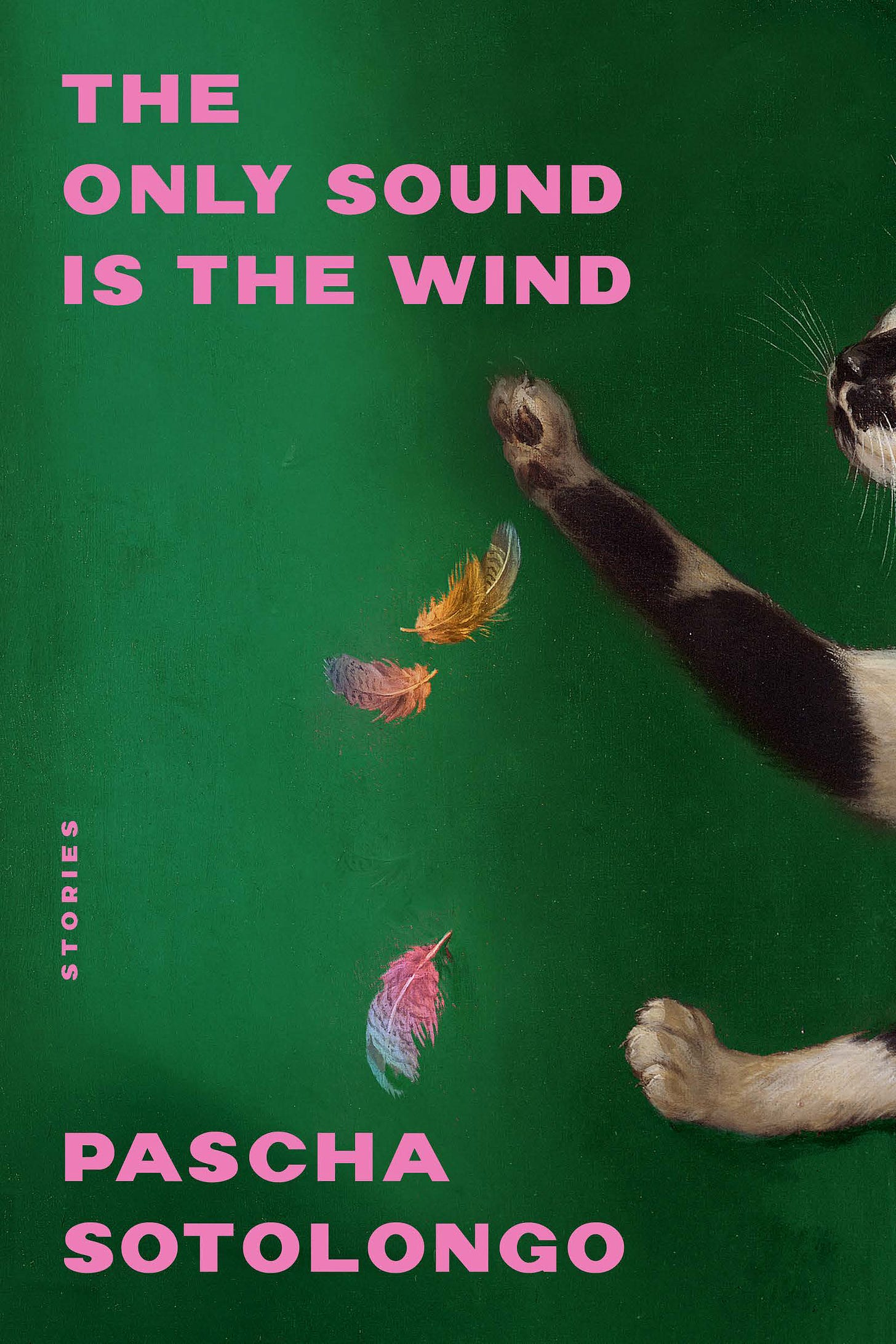

Pascha Sotolongo brings some to America in her short story collection The Only Sound is the Wind

The unknowable hangs over each of the stories in Pascha Sotolongo’s collection “The Only Sound is the Wind.” Something can’t be explained. One could call it magic, but I prefer supernatural. The stories move through America — mainly the mid-West — and the characters are loners searching for belonging. Each story haunts the pages.

My favorite story, “Shoelace, Camisole, Rope,” is about a young Cuban girl in Miami dreaming of eating pastries from a bakery. It opens with a line that sticks the reader in a place and grabbed me.

“Yulia cupped her face against the glass to block out the Florida sun.”

Yulia hangs outside the window “preparing to make a deal. It was serious business.” She knows she can’t have the pastries. She can’t afford them. Her grandmother can’t either. Her family can’t. Plus, they’re not part of their culture. Those pastries don’t work. They’re of the other. It’s a moving portrait of community, youth, loneliness and the possibilities that don’t afford themselves to everyone in America. It’s a perfect encapsulation of the stories in “The Only Sound is the Wind,” which breathes through characters trying to understand their identity and their place in the world.

Sotolongo brings in elements of the fantastical, but only just enough to bring her stories to another level. She avoids using “magical-realism” to explain or to give readers an easy way out. Instead, she uses it to enhance the feeling of isolation that simmers on the surface and boils underneath each sentence.

"The Only Sound is the Wind” is Sotolongo’s debut collection.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

These stories are about often people feeling displaced or searching for their identity in a place. They're Cuban in the Midwest or Cuban even in Miami, which would seem relatively straightforward, but isn't. So what was your launching off the point for these stories?

That does come up a lot. There may be something mundane about tracing everything always back to one's childhood, but I think some of it comes from being really nomadic. When I was growing up, we moved a lot and those they weren't really guided moves. My dad wasn't military or something. He was just trying to find himself.

For me, my father was always modeling a sort of perpetual displacement and looking for the new place to give him a context or a sense of himself that suddenly made sense, and that enabled him to kind of settle down in the world and with himself. I was really influenced by my dad, so I think that's probably the original seed of that scent.

We moved a lot and some of that also became part of my identity. People often asked me, “do I feel like a Nebraskan now or do I feel like a Midwesterner?” because I'm originally from Florida and I've been living here in the Great Plains for a long time, but you know, I never feel like I'm from anywhere. I just don't feel like I'm from anywhere. I mean, Florida's the closest because I was born there, but I think I have a rooted a rootlessness about my own identity and I think some of that got expressed in those stories.

Well, even Florida is kind of a rootless place, right? Florida is a place where people go. Either they retire or they end up there for some reason. A real Floridian is somebody whose family has only been there for a few generations, right? I always joke with my parents that it’s a swamp and the only reason people live there now is because of air conditioning. It's a swamp and we've had to straighten rivers and ruin rivers for for people to be able to live there. So how does Florida influence you then in this displacement? Of people searching for themselves?

That's interesting that you say that. I will offer this: my my mother grew up very, very poor. My dad's a Cuban, but my mom grew up very, very poor and my mom's white and she remembers that there was no air conditioning. There was no air conditioning in her elementary school. There was no air conditioning at home. There was barely anything and she's not so old. I mean, she was a kid in the 50s and 60s. So, I would just say, that I think you're right about air conditioning and, yes, now Florida is populated by people from all over and obviously people have been retiring there for generations, but when I was growing up, I remember seeing bumper stickers that said “Native”. It would have the shape of Florida and then the word “native,” like this brag, meaning you're from Florida, you were born there, or maybe your family was born there, and somehow that distinguishes you from the people who are sojourning or people who have just arrived. So I can remember that being this weird thing, which was not something my family would have ever done.

But you know, I have so much affection for Florida, but it's a sort of a strange place. Growing up there, my family was always trying to sort of find the places that weren't so commercialized and weren't so exploited. I mean, the land there, obviously, has been, as you say, sort of forced into accommodating our needs, our population needs. That's to put it mildly.

It's a need for capitalism. Somebody needs to make money.

Exactly. And it has not been kind to the land at all, or the the ecosystem.

So we were always trying to find those out of the way places. When I remember Florida, that's what I remember: these quiet places, these little, sleepy spots, you stop off at a gas station to grab some sort of cheap refreshment and the parking lot’s gravel and there's sand inside on the floor and there's a jar of pickled pigs feet by the cashier, that kind of thing. We would go to the beach and it was the state park, and it tended to be kind of quiet and was restricted and free, but there were no condos or anything built up.

So when I go back now, there's always sort of a shock to the system because Florida for me is a temporal location. It's not a physical location anymore. It's gone. And it's it's part of my past. When I go back, I feel like there's a strong displacement just based on the passage of time, which is really common. I know people go back and everything changes and it's gone. But there's something surreal about Florida because it engages in this ongoing simulacra, there's just so much there that's artificial and bigger than life, and, yet, what's real there is is so stunning, if you can still find those those bits.

There's something about Florida that is kind of special.

It’s a place with plenty of stories. There's no shortage of people you meet to write about. I can picture people just at the airport and I'm like, that is a story.

I found it interesting when you said sleepy, small town, because in your stories have a sense of those things and it is why I was drawn to reading them as about identity, because the other part of that experience is that the stories seem confined to a space, a place that feels alive in its own way. There is some magical elements to the stories because of that.

The tight structure in your stories fits that confinement. They feel almost claustrophobic, which I enjoyed because you're not trying to reach beyond. It's like this is here and we're we're going to stay in the moment. So how does that come about for you?

I think that in this particular collection one of the reasons that's the case is that I was really meditating on isolation. I'd been reading a lot of articles the pandemic of loneliness and isolation well before COVID. So I was I was thinking about that and increasingly, I don't know, aware of sort of a general human choice in the United States, but even somewhat globally, in particular kinds of societies to not connect so much or to stay home more or to be in isolation more. As recently as just a couple weeks ago, there was an article in The Atlantic on “The Anti-Social Century”.

Some of it came from a meditation on isolation, and I think that is necessarily going to put you in smaller spaces, give you a feeling of just there being almost in a vacuum because you're spending time with people who are, for various reasons, electing to be in that sort of smaller sphere. Sometimes I feel like I'm not sure if I can ever see my own writing anyway, but I tend to think of myself as more scene driven as a writer and so there's also that sense of really exploring, you know, a particular moment in time and letting it expand out. And, as you said, almost almost kind of magical ways, and that sense of going deeper rather than sort of broad, rather than covering territory.

It's almost as if you go into an internal life of a person through the scene as opposed to creating internal monologues that are running for pages. It's more like, here is this place and this place partially defines them while they're searching for something else. Right? And it's it's through that internal discussion that, as I said, it feels confined and reaching in as opposed to out. So what what what draws you to that kind of story? Is there is there something that kind of sort of sets you in that direction just by accident or on purpose?

No, I mean, I'm sure it's not an accident. I think some of it is deliberate.

As I said, I'm always interested in sort of social evolution. If you tell stories, I think you're interested in people, and, if you're interested in people, you're interested in sort of these intimate ways, but also kind of writ large. And so some of it was definitely that interest in what I was reading about isolation and thinking, but some of it's probably personal.

Growing up, I was an only child and my parents and I moved a lot, as I said already. So some of it was kind of having to survive those times of being isolated because, at times, I was isolated growing up. I was homeschooled and other times I went to public school, I went to parochial school.

We were always moving and I pretty much always had friends because we always lived in apartment complexes, so that was really nice, lots of kids always there. That helped, but some of it probably comes from those periods of isolation and adaptation. And then reading about, over the decades, the amount of time that we’re increasingly spending alone by choice, which is really interesting to me because I don't actually prefer alone time. Except for writing, I don't really prefer to be alone. So that wa an intellectual fascination as well.

I'm reading Nicholas Carr's book “Super Bloom”, which examines mass communication as something that was supposed to bring us closer, but every time we've gotten a new type of communication it's pushed us further apart. I'm thinking about what you're saying about being alone and all these various schools and having to make friends and it is interesting to me that these stories take place in a very personal space Or there's somebody watching somebody from a window and wondering about someone else outside. I'm wondering, as you're moving around as a kid, how much that influenced your writing because as a kid I was always creating stories about people. I still do it today. My wife set up a Rover account after we put our dog down so we could have dogs without having to buy a dog and I always have a story for the people that drop their dog off. She's like, do you just always psycho analyze everybody that comes in the house? And well, yes, I've kind of always done this. I'm wondering if that's something you were doing?

Yeah, that's a really interesting question. Sounds like you might need to write a novel.

Well, I'm just about a person that watches dogs and then make stories up about other people. But is that something you were doing as a kid? Is it something you remember doing?

Honestly? Not much. As a kid I wrote poetry.

We all want to be a poet. I swear every writer wants to be a poet and it's so hard.

It's so hard. I'm so intimidated by poetry. I think poets often make brilliant writers. I'm certainly not a poet. I mean, I wrote poems as a kid. I've not written poems as adult, except occasionally on my mom's birthday I write a poem and she thinks it's wonderful, but I don't let that go to my head. But, you know, I didn't much. I mean, I did imaginative things like a lot of kids. I played in my imagination a lot, but I also spent a lot of time outdoors, fishing and, being in boats and going to the beach and, hanging out with friends and doing a lot of those regular things. So I wasn't really a storyteller. I was fairly reserved in some ways, but gregarious as a player and like running and physically I was pretty gregarious. But I wasn't really a storyteller.

I played sports, but inside my head there's other things that are happening as people are talking or as I'm moving in that world.

Yeah, that's a fair point. But that just wasn't me. I mean I listened well. I paid attention well, but I didn't really think in terms of story too much until later.

The poetry was a way, I think, to be descriptive about the world and capture certain emotional moments, and capture the emotional weight of things. So, I guess that's a form of storytelling, though, it wasn't particularly narratively driven. I used to act out the scenes of the books I was reading, so I would do that as well, which is sort of a form of storytelling because it was always embellished and taking liberties with “Jane Eyre” or whatever. So not really a storyteller until considerably later.

You have a PhD in literature and, first off, congratulations. I looked up how to do that and that's really hard. What did you study? What was your interest?

It's interesting because I went to school entirely on student loans and grants — Pell Grants, that's how poor I was before college, that I qualified for a Pell Grant and student loans. And I felt like I was always trying to find my way between making practical choices that I thought you should make if you grew up if you were poor and you were going to have all this student loan debt versus what I really wanted to do. So somewhere along the line I got into my head that to study creative writing was an indulgence that I couldn't afford because I wasn't connected and I didn't have any money and I was going to have all the student loan debt. That's why I wound up pursuing the PhD.

I don't regret the PhD. It was a great experience. I loved it. I studied mostly Caribbean writers, Caribbean women writers and some post-colonial theory. I was interested in kind of, I don't know, like Neocolonialism through tourism and marketing as it was expressed in literature. Sort of feminist and post-colonial and looking at the contexts for reading women's bodies in the particular set of texts that I was examining.

But when you get a PhD you take lots of classes besides what's in your dissertation and so it was a good experience, but I never got an MFA or anything like that.

I have one. It's fine.

Yeah.

It's whatever. It's whatever. I have loans again. Bu it's what you make of it, right? Like all these degrees. For an MFA, I think the biggest thing is my teachers made me read things I wouldn't have read and think that, for a writer, is more important than anything. Because you get taste and to study a topic and a topic is important.

Do you see yourself looking back can you see where these stories or this reading, even if it's off your track, is influencing what you're doing now?

You know, I think, particularly in terms of finding a kind of a magical realist style because that's not something I'd read a lot of as an undergrad. I found myself as soon as I read Cristina Garcia's “Dreaming in Cuban”, which is from the 90s, but I did not encounter that book until graduate school. It would have been like the early 2000s in my PhD program. Finding that book was really eye opening for me because I was my dad was always watching “The Twilight Zone” and things like that and “Star Trek”, and I was always drawn to speculation and to sort of weirdo kinds of things that were in my head, that was the only word I could come up with. Then, when I found these writers doing these really brilliant things with realism, but with these kind of overlays of magic and a certain degree of speculation, to me, that was really exciting and liberating. I started seeking out who else had done that in the past or who else was doing that. That was, liberating is the only word I can come up with. That was really liberating.

I think we're going to see a wave of some magical realism coming out of the United States. I read “The Bullet Swallower”, which was has those elements. It's a Western with that feeling of magical realism. There are ghosts, things kind of coming in and going. In the same year I read “The Master and Margarita” I think books like this come out of places where you're oppressed in a way. You have to create something to to express that oppression and you can't use the every day because then you end up dead or exiled. You come up with these things, and I have a feeling that might be happening soon.

So I'm wondering, you know, for your stories, do you feel like you're almost ahead of the game here then a little bit, right?

There are so there are so many Latin American women writers, in particular, who've been writing this brilliant magical realism. I'm just thinking about like Claudia Donoso, “Little Bird” is one of my favorite collections. It's brilliant and it's really magical realist. Samanta Schweblin is another one.

I don't even know that my style is magical realist, but I know I've taken something from that. But I seriously doubt that I'm ahead of anything actually, to be candid.

You know, I just have to say, though, that I think there is something that feels surreal about growing up poor. There really is. I watched my father struggle to explain what poverty was, to explain how he was experiencing poverty and experiencing it on our behalf. I watched him puzzle. For him, poverty was like this huge question. We would look at people who had money and just sort of puzzle and be like, but how do they have it? Because we were working hard and I've worked pretty much since I was 10. Started out cleaning apartments when I was really young. We were working, but we didn't have the results.

And after a while of doing that, it genuinely starts to feel surreal.

So there's also that the way in which I think magical realism or surrealism or whatever you want to call it, helps almost realistically capture experiences that just defy representation because they're so complex, because they're so frustrating, overwhelming. They're just so enigmatic. When you're living it, you can't explain it. It feels unreal.

Yeah, it's that's a really good point.

I think if you're really dialed into your parents then you can see it. My dad, as I've already illustrated probably too much, I was seeing it register in him. I could feel that it was concerning, it was concerning to be poor because I could see how much it was beating down this really talented, charismatic person, this man. So there was and there were times when we were poor enough that we weren't sure about where we were going to live. We weren't sure if the electricity would be turned off, things like that. The food got really low. So, I mean, at times when you're a kid, when it comes down to that, you're like, yeah, I can feel this because the house is cold and it should be warm.

But that didn't happen that often, and at times we were middle class. It was really dynamic.

But all of that contributed, I think, to a sense that a surreal narrative is really the only way to capture the craziness of what this feels like.